georgemiller

Publish Date: Mon, 30 Sep 2024, 07:30 AM

Key takeaways

- The RBI has been rattled by credit outpacing deposit growth over a prolonged period, and the changing composition of both.

- A recent easing of liquidity conditions and higher base money growth will likely push up deposit growth over time.

- However, to change the composition of deposit and credit, real economy intervention will be necessary.

Through the summer, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has articulated its worries about weak deposit growth, the rising credit-to-deposit ratio, and compositional shifts (too much unsecured lending, too few sticky deposits) that could hurt financial stability.

Many reasons have been attributed to weak deposit growth. But most of them do not stick. Strong inflows into mutual funds could not have cannibalised deposits, as the money stays within the banking system (even if it switches accounts). Currency leakage can’t explain weak deposit growth either, because the ratios have been moderating.

Then what explains it? Deposits have two creators – money created by the central bank (known as base money, M0), and money created by the commercial banks (through the money multiplier process). The money multiplier can’t explain the weakness. Rather, the multiplier has gathered pace over the last few years. So then, the weakness in deposits must come from M0 growth. And, indeed, M0 growth has slowed over time, even running below nominal GDP growth.

Why would the central bank slow M0 creation? For most of the last two years, inflation has been elevated, the dollar has been strong, and the RBI has been running tight monetary policy – raising rates with a hawkish “withdrawal of accommodation” stance, which is associated with tight liquidity. Meanwhile, delays in government spending due to the new just-in-time accounting framework have also kept liquidity tight.

But all of this has changed recently. With the heatwave ending, inflation is converging towards target as per our forecasts, unsecured lending has cooled off, the dollar index has weakened in recent weeks, the RBI’s FX reserves have risen, and the government has ramped up spending. Some of these factors have arguably made the RBI more comfortable with faster M0 growth, while others have already raised M0 growth and eased banking sector liquidity in recent weeks. If this sticks, deposit growth could begin to tick higher, resolving half of the RBI’s worry.

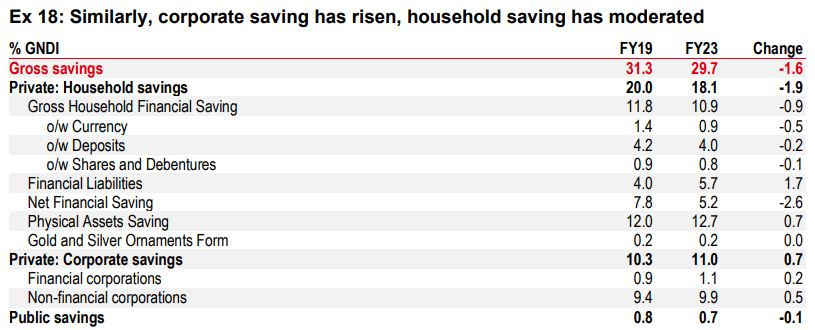

However, it may be harder to resolve the composition issue. With rising profitability, corporate saving has risen, resulting in higher callable bulk deposits, while household financial saving has moderated, resulting in weaker sticky deposit. All parts of the economy are not doing equally well and higher corporate profitability in some sectors coexists with weaker mass consumption. The latter has kept private investment and demand for capex loans softer than personal loans (some of which are unsecured). Addressing the two-speed economy issue with reforms will thus be key to resolving the other half of the RBI’s worries sustainably.

Summertime debating

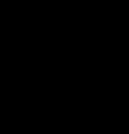

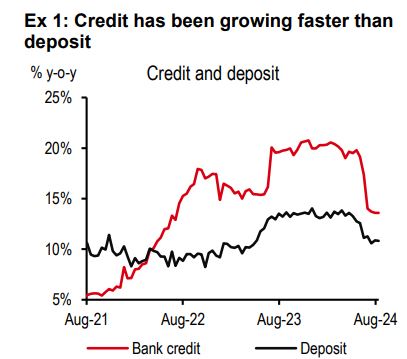

It’s been a long summer, with policymakers, especially the RBI, articulating at various forums over the last few months, its worries around the imbalance between deposit and credit growth at India’s banks. Credit has been growing faster than deposit growth for the last 30-odd months (see Exhibit 1). No surprise that the credit-to-deposit ratio is elevated (around 80% versus a pre-pandemic average of 75%, see Exhibit 2).

Why is this even a problem? An elevated credit-to-deposit ratio tends to autocorrect over time. And, already, there are signs of credit growth softening, leading to some moderation in this ratio.

The worries seem to be at a deeper level. It’s not just about the growth in deposit and credit, it is also the composition that is bothering the RBI.

On deposits, in the August policy meeting statement, the RBI’s governor said that “banks are taking greater recourse to short-term non-retail deposits and other instruments of liability ...”. This could “expose the banking system to structural liquidity issues.”

On credit, the RBI has been concerned about the rapid rise in unsecured lending. While that is gradually slowing, it continues to remain concerned about “excess leverage through retail loans, mostly for consumption purposes”.

In this report we drill into the root cause of this problem, and the connections with the RBI’s monetary policy stance. Thereafter we discuss when and how will this issue be resolved. We find that half the problem is already getting rectified as the RBI comes closer to softening its hawkish monetary policy stance.

The other half of the problem, namely the composition of credit and deposit, is more complex, with roots in India’s growth composition and saving behaviour, and will require ‘real economy’ intervention, a la economic reforms, rather than just financial nudges.

How did we get here?

Let’s start with the weakness in deposit growth.

Many reasons have been attributed to this weakness. But most of them do not stick.

Are strong inflows into mutual funds cannibalising deposits? Not really. If one household takes out money from banks and invests it in mutual funds, some other household makes the underlying shares available, getting a cash deposit in return. Adding up across households, bank deposits remain unchanged. The same, broadly, can be argued for other financial assets like bonds, insurance products, and even property.

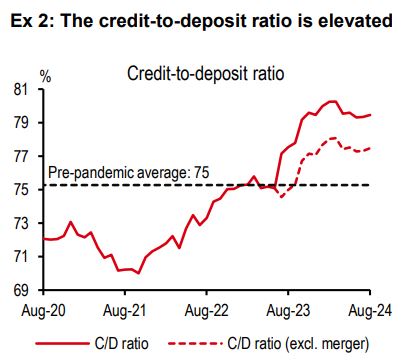

Is currency leakage hurting banking sector liquidity? Again, no. Because, as a percentage of GDP, currency in circulation has been declining back to pre-pandemic and pre-demonetisation levels (see Exhibit 3).

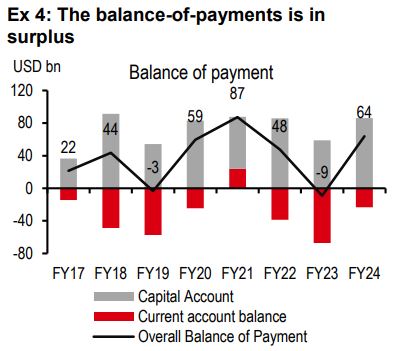

Is weaker foreign equity ownership leading to deposit outflow? Not at all. True that the ownership share of foreigners in India’s equity markets has fallen, while domestic participation has grown. However, when we add up all the engagement India has with the rest of the world, across exports, imports, capital inflows and outflows, which is well captured by the balance of payments, we find it to be in surplus, and a growing surplus at that (from USD48bn in FY22 to USD64bn in FY24; see Exhibit 4), courtesy of strong services exports and portfolio debt inflows.

Whodunit?

So, what’s really been driving the weakness in deposits? Let’s think through the monetary system carefully.

Taking a careful view of how monetary systems are interconnected, it is clear that deposits have two creators – money created by the central bank (known as base money, M0), and money created by the commercial banks (through the money multiplier process, i.e., the credit creation process).

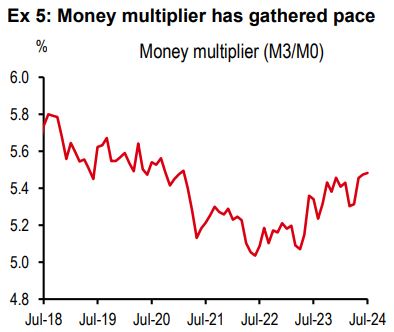

And here, the money multiplier (calculated as M3/M0) can’t explain the weakness. Rather, the multiplier has gathered pace compared to the pre-pandemic period (see Exhibit 5). This is consistent with the strong credit growth over this period.

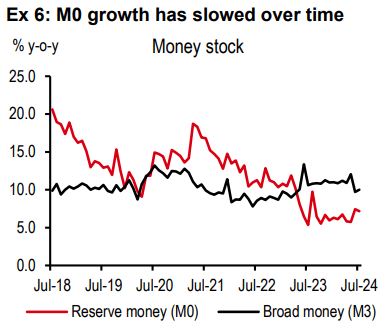

So then, the weakness in deposits must come from the weakness in M0, which the central bank creates. And, indeed, it is clear that M0 growth has slowed over time (see Exhibit 6).

The RBI’s reaction function and money creation

But why would the central bank slow M0 creation. Let’s dig deeper.

We believe a few factors influence the level at which the RBI wants to maintain M0.

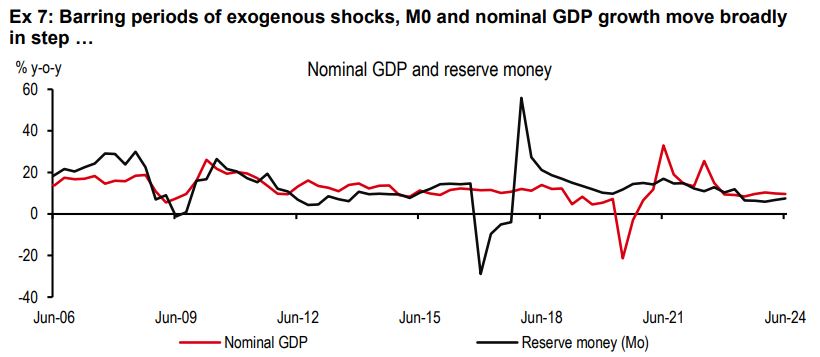

- Nominal GDP growth. The RBI endeavours to provide enough liquidity to meet the productive needs of the economy, which is easily proxied by nominal GDP. Indeed, barring periods of one-off shocks, M0 growth and nominal GDP growth have moved closely (see Exhibit 7).

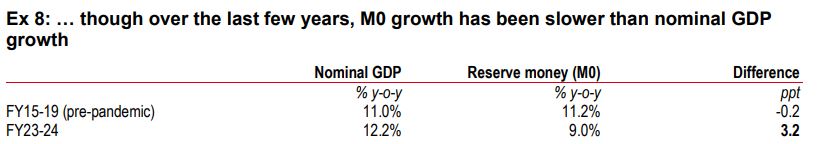

- An element of discretion. The RBI can choose to keep liquidity tight/loose to help with its objectives like inflation management, financial stability, etc. And, indeed, we find that over the last two years, the RBI has preferred tighter policy (more on this later). M0 growth has been running a shade lower than nominal GDP growth (see Exhibit 8).

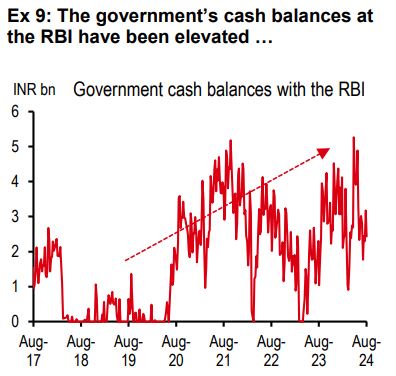

- The government’s larger-than-before balances at the RBI. The government has been rather tardy with expenditure. And it has its reasons. The central government has moved to a just-in-time accounting process, whereby funds are released to the states only when needed, promoting the efficient use of resources, and reducing the cost of idle funds.

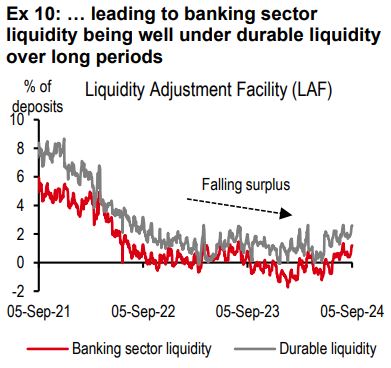

This has changed the government’s spending schedule; much of the spending now happens later in the year. And, while the money eventually gets spent, it first remains locked up for several months in a row (see Exhibit 9). This is clearly visible in the large gap between banking sector liquidity and core banking sector liquidity (which includes government balances at the RBI; see Exhibit 10).

To summarise, the weakness in deposit growth has been influenced by softer M0 growth, which, in turn, has been influenced by endogenous factors (like GDP growth and inflation, and the RBI’s objective regarding them), as well as exogenous ones (the government’s new just-in-time spending framework).

But it’s all changing quickly

But this is a story of the past. It’s all changing quickly, as we speak.

There could have been a few reasons why the RBI kept M0 growth on the weaker side for the last few years. One, inflation was well above target, both in India and in the rest of the world. The RBI was hiking rates with a hawkish stance – a removal of accommodation. Two, the dollar was strong, leading the rupee into bouts of weakness. Arguably, the RBI had a preference for keeping monetary policy tight as an interest rate defence during this time. And three, credit growth was strong, and that as well, in areas the RBI was not comfortable with, like unsecured loans.

But each of these have now reversed quickly:

- Core inflation has been below 4% for the last seven months. Food inflation has finally begun to fall and will likely continue to fall. We find that normalising temperatures since the March heatwave will likely raise crop output and lower prices, with headline inflation at 4% by year-end 2024; this, we believe, will open the door to the RBI officially relaxing its ‘removal of accommodation’ stance and cutting rates. We expect 50bp in rate cuts starting in 4Q 2024, taking the repo rate to 6% by March 2025.

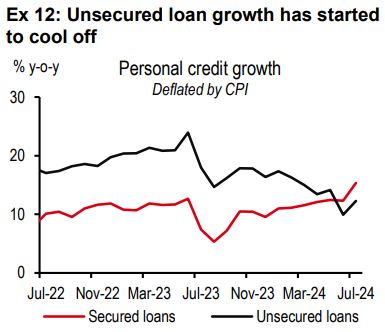

- After a spell of strong growth, which rattled the central bank, unsecured lending growth has started to cool (see Exhibit 12). This could provide the RBI with some confidence to allow base money (which forms the basis of credit growth) to grow more rapidly than before.

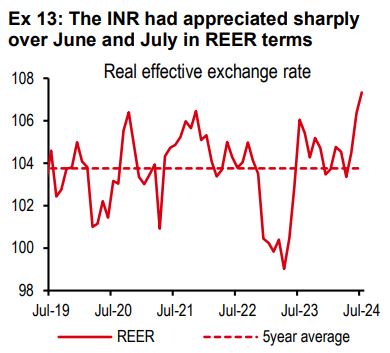

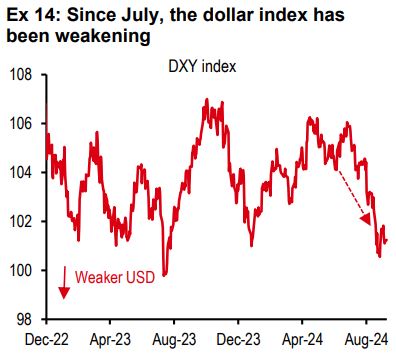

- The dollar has weakened in recent weeks, providing much needed breathing space to emerging market economies. India, for now, seems to be using this opportunity to accumulate foreign exchange reserves (with foreign currency assets having risen by USD30bn since June), perhaps in a bid to reverse the sharp REER appreciation over June and July (see Exhibit 13 and Exhibit 14).

- The government has ramped up spending post-elections (see last few observations in Exhibit 9 above), not just spending tax receipts, but also the RBI’s dividend it received a few months ago.

In fact, the RBI buying foreign exchange reserves and the government spending from its account at the RBI are ways to raise base money growth. Indeed, M0 growth has already risen from 5.8% y-o-y (over April and May) to 7.3% y-o-y (over June and July).

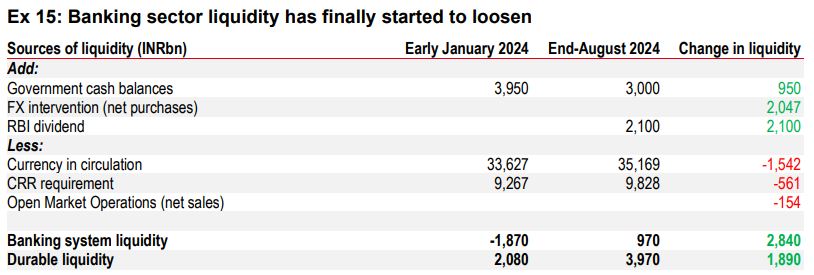

And, relatedly, banking sector liquidity has perked up in recent weeks, leading to market rates at the short end softening by 25bp (see Exhibit 10 above and Exhibit 15).

So, will the RBI’s problems be solved?

Yes, at least half of them. Let’s take them one at a time –

Deposit growth? Yes

With base money having risen recently and likely to rise further as the RBI moves from tight to neutral/loose monetary policy, deposit growth could get a shot in its arm.

Credit-to-deposit ratio? Perhaps

It’s harder to postulate whether the credit-to-deposit ratio will fall, as desired by the RBI. At first glance, if deposit growth rises, the ratio must fall. However, looking deeper, higher deposit growth could also make funds available for higher credit growth (assuming no fall in the money multiplier).

Composition of credit and deposit? Not so easily

Alas, this is where no quick solution seems visible. The RBI has been concerned about compositional shifts. Too much unsecured lending on the credit side. And too few sticky deposits and too much callable bulk deposits on the deposit side.

Some short-term interventions have helped and could continue to help. For instance, higher risk weights since November 2023 have lowered the pace of unsecured loan growth already.

However, these would be partial fixes. The reason the composition has gotten skewed lies in the real economy and will require real economy fixes, not just some financial nudges.

It’s the real economy

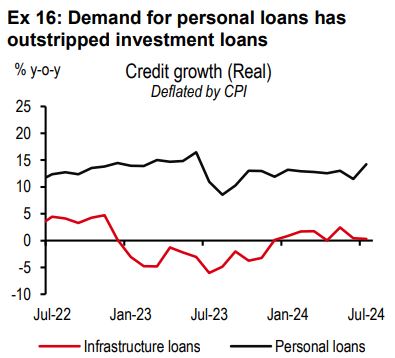

On the credit side, demand for personal loans has far outstripped demand for, say, capex loans (see Exhibit 16). Private capex is not firing on all cylinders. Investment in machinery and equipment is weak. Weak mass consumption is likely coming in the way of factories adding capacity. As such, weak mass consumption is the problem that needs fixing to change the composition of credit.

On the deposit side, there is a noticeable rise in corporate deposits and a fall in household deposits (see Exhibit 17). This maps well with India’s saving data, whereby corporate saving is above pre-pandemic levels, driven by strong profitability in certain sectors, while net household saving is lower than before (see Exhibit 18).

This is partly reflective of a two-speed economy where some sectors are growing well, but all the gains are not flowing down to mass incomes.

In short, to improve the composition of credit (more capex loans, less personal loans) and deposit (more retail-led CASA deposits, less corporate bulk deposits), the economy needs to support income growth across the pyramid (low-, mid- and high-tech sectors).

This will require careful and timely reforms. One of them being making the most of global trends whereby many companies are trying to rejig production supply chains. Actively pursuing FDI in low- and mid-tech sectors like textiles, food processing, and toys, which tend to be more labour intensive, could raise both investment, as well as wages and incomes.

https://www.hsbc.com.my/wealth/insights/market-outlook/india-economics/2024-09/